A BRIEF HISTORY OF FASCIA

MASSAGE

CÉCILE DUMONT SHARES WITH US THE FASCINATING HISTORY OF FASCIA

In the past 20+ years, research on fascia has exploded and it has become the focus of a multidisciplinary research that goes beyond a purely anatomical approach and now reaches into the intangible. Yet as we learn more and more about this mysterious Cinderella tissue, we are still unclear as to what it really is, does or how to define it. Shall we talk of ‘a fascia’ (singular), use its plural ‘fasciae’ or refer to it as the ‘fascial system’? Is it a tissue or an organ? An organ system? Or even an organism? It would appear it is each and all of these at once.

Thanks to the Fascia Hub, I recently attended an incredible lecture by Dr Sue Adstrum, an integrative anatomist, researcher and writer who has spent half of her life exploring anatomy dictionaries, textbooks, monographs and archives searching for the meaning of fascia. She invited her attendees on a journey through time to look at its history, a long and rich history that shows us how its perception has evolved through time. This one-of-a-kind connective tissue has so many facets that it makes it almost impossible to pinpoint or classify it under one simple neat definition.

Before diving into this brief history of fascia, I will, however, leave you with one of my favourite analogies offered by Joanne Avison, structural anatomy teacher extraordinaire – fascia as the original and exceptional fabric of our human bodies; a living continuous ubiquitous and sensory fabric that incorporates and organises all aspects of us.***

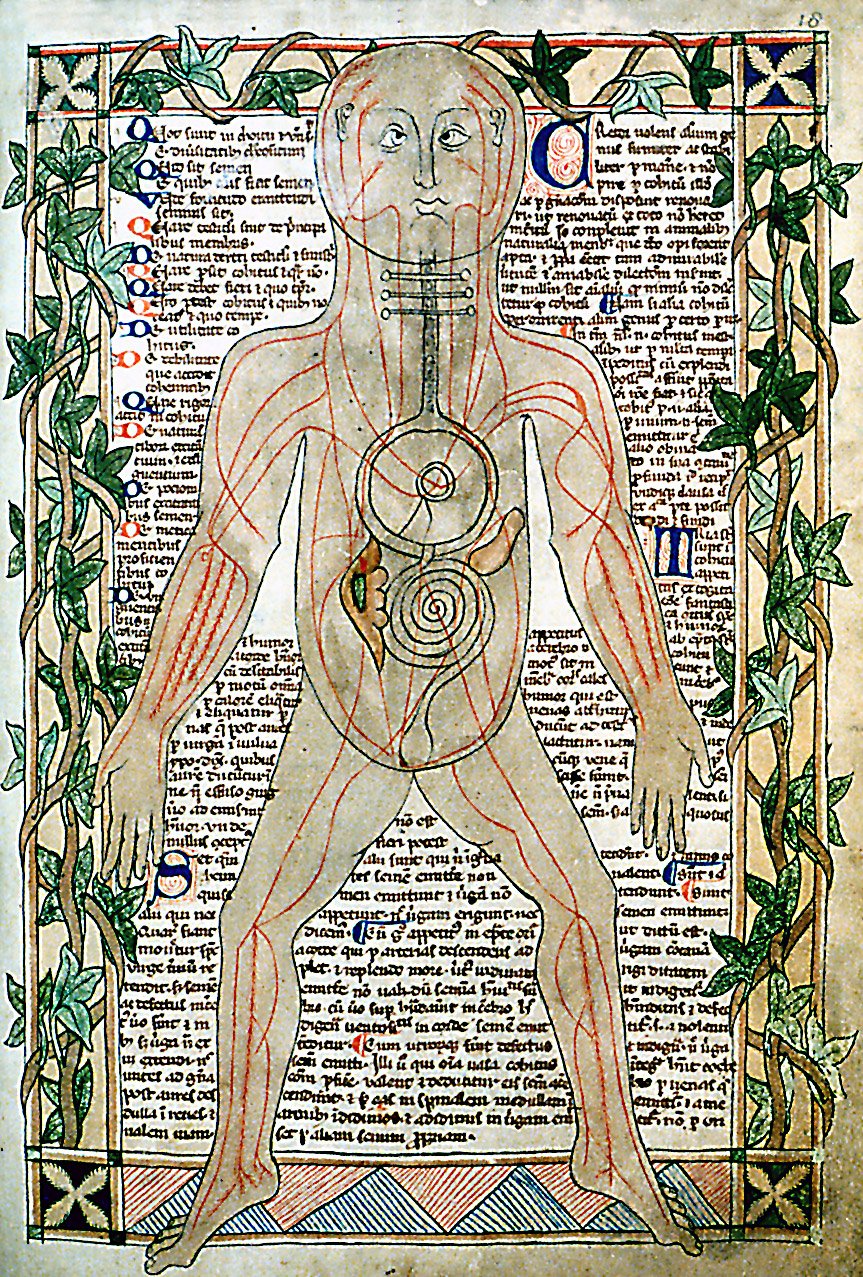

References to fascia can be found as early as 3000BC in Ancient Egypt where membranes (not yet referred to as fasciae) appear on stone tablets later passed onto papyrus that was preserved to this day! Travel through time and space and you reach Ancient India circa 600BC where dead bodies were left to progressively rot in water, and layers after layers were brushed away so as to study the human form, thus proving the awareness of the concept of connective tissue. An awareness that also appears in Ancient Greece where the Alexandria School of Medicine and Anatomy mentions tendons and ligaments in its studies.

The word fascia itself makes its first anatomical appearance under the Roman Empire with Galen of Pergamon using it to describe the attachment of muscles also known as ‘origins and insertions’. It is a Latin word that derives from the Greek taenia and means ‘string of fabric’. Up until then, it had been used exclusively in the textile industry.

If the Middle Ages in Europe didn’t bring any new knowledge in the field, it is the Islamic Golden Age (800-1300AD) that brings to light for the first time the sensitivity of fascia and its sensory nature. It isn’t until the 16th century in Europe, where dissections remain mostly prohibited, that anatomists start to understand that the body, and the body only, should be their textbook, and that it will be their greatest teacher. Thomas Vicary publishes the first anatomy textbook in the English language describing ‘membranes and skins’ but not yet using the word fascia in his translations. To find the word fascia in an English text, we have to wait until the 17th century and Helkiah Crooke, who translates the most important anatomical texts from Latin, and describes fascia as “the organ of the sense of touching”, soon joined by Samuel Collins and his “garment of the body”.

As time passes, more words are being used to describe fascia based on its function or where it is in the body (aponeurotic, tendinous, muscular, fascia lata, fascia lumborum, etc). And it is the development of microscopes in the 18th century and Xavier Bichat’s Treatise on Membranes, that now see fascia referred to as cellular tissue – it is no longer the tissue that is being brushed or scraped away in dissections but it becomes an object of growing interest under the microscope.

However, the development of embalming techniques in the 19th century and particularly the use of embalming fluids puts a hold to any further relevant research as it dehydrates the fascia and turns it into a thick hard layer, which prevents it from being accurately observed and studied. It isn’t even mentioned in medical training and fascia keeps being painstakingly cleaned away for a “good” educational dissection. Hence the Cinderella reference at the start of this post – fascia was “the most ignored of all the tissues in the body – at least up until recently” declared Tom Myers, a contemporary pioneer in the field of fascial research and manual therapies.

It nevertheless becomes a matter of interest to surgeons, and Andrew Taylor Still (1828- 1917), physician, surgeon and the founder of osteopathy, attributes it a major role for the first time in Western medicine declaring that “fascia sheathes, permeates, divides and subdivides every portion of all animal bodies […] By it actions, we live, and by its failure we shrink, or swell, and die.” He claims that when it comes to understanding the human body we need to know the parts as well as view the whole, and that everything is indeed connected. A revolutionary concept at the time and an approach that will become Ida Rolf’s legacy in the 20th century as she develops Structural Integration and brings fascia, “the organ of posture”, to the forefront of manual therapies.

Research has tremendously accelerated in the 21st century with the development of new technologies culminating in the Fascial Plastination Project, a collaborative journey to create the world’s first 3D Human Fascia Plastinate. This unique achievement, directed by fascia research scientist Robert Schleip, professor of anatomy Carla Stecco, with the assistance of clinical anatomist John Sharkey, led to the unveiling of a full-body fascial plastinate on November 24th at the Bodyworlds exhibition in Berlin (see below for a link to the unveiling if you are so inclined). ***

After thousands of years, fascia remains a mysterious and fascinating tissue. And its research has a bright future ahead as mankind keeps trying to pierce its secrets. A part of me hopes we won’t uncover them all…

References

* Adstrum, N.S. (2015a). The Meaning of Fascia in a Changing Society. University of Otago, NZ (PhD

thesis)

* Adstrum, S. (2021). The Living Wetsuit. Auckland, NZ : Integrative Anatomy Solutions.

* Avison, J. (2021). Yoga, Fascia, Anatomy and Movement. 2nd edition. Edinburgh, UK : Handspring

Publishing

* Link to the unveiling of the full body fascial plastinate unveiling – https://m.youtube.com/watch?

v=Huv3_QwdbWQ&feature=share&fbclid=IwAR2d5dhUF3YIYyZ7-TR5zyHe7iHyZDGuZ_yVMU-