Fix’s sport massage therapist and osteopath-in-training Sanja tells us why you needn’t put up with grumbling shoulders and how better to love your scapula!

A whole year of studying anatomy has passed and it still surprises me that our shoulder blades (our scapulae) have seventeen muscles attached to them. That’s right – 17! That makes our shoulder blades pretty important when it comes to shoulder mechanics and function but therefore it also makes them a common site of pain and soreness.

Shoulder blades play an important part in shoulder joint articulation and your therapist will often have a hunch about what is wrong with your shoulder just by looking at the position of your scapula. It says a lot.

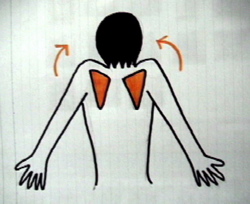

All seventeen muscles perform a range of different movements during which they take the scapula, or the part of scapula they attach to, into different directions. This means that our scapula is constantly getting pulled into different directions.

Really?

Or rather, does it mean that it is being pulled into the position of the muscles that work the most, then it gets trapped and stuck in that position.

What we actually want is harmony and balance between all seventeen muscles in order to have a healthy, happy shoulder.

So, how do we achieve this? Here are some things you need to know about your shoulders:

1. First and foremost: it is not acceptable or normal that your shoulders hurt.

More so than with any other joint, I find clients tend to accept that this, for some reason, is normal and that their shoulders niggle from time to time (with knee pain being on the second place on this list). Some fatigue and tightness is, of course, normal after a long day at work but when you are sitting at your desk, practicing yoga or running, your shoulders should not be in discomfort or produce twinges and niggles. If they do, then it’s time you do something about it.

2. What makes good (shoulder) posture?

Imagine our body as a building with our feet being the ground floor, the knees the first floor, hips second, lumbar spine third, thorax and shoulders fourth and the neck the fifth floor with head being the roof. All floors need to carry their share of the load or the building will become unstable.

In human body language, this means that each mentioned joint, or joint complex, needs to be able to support the right amount of amount of body weight. If it doesn’t then the additional strain and overload can result in muscle tension, pain and dysfunction. This also means that each ‘floor’ will be influenced by the position of all other floors.

Here is a basic plumb line assessment that you can do at home: Stand side on in front of the mirror. Now imagine a plumb line falling vertically from the centre of your ear, down through the midline of your shoulder, through the little prominent bump on the side of your hip, side of your knee (make sure your knees are soften and not locked) and down just forward of the bump on the outside of your ankle. If your line is does not go through these points then your posture is not as optimal as it could be.

When the points are lined up, the line ensures you are centred and your weight is distributed equally throughout your body. Practice this when standing at the station and waiting for a bus. It feels great (if not a little odd, like you’re in no-mans land, to start with). Your body will be grateful.

3. The big question: Shall I put my shoulder blade back and up or back and down?

This is a question I often hear my patients asking and it seems like it is creating a common confusion out there. You don’t really want your scapula back and too down as this can cause a lot of traction through your humerus (your arm bone) and make the rotator cuff muscles (especially supraspinatus) work too hard – potentially resulting in a tendinopathy or tear. On the other hand, by putting your shoulders back and up, clients tend to over tense their upper trapezius, which can than compromise the mechanics of your neck. Ideally you want your shoulder blades back and slightly upward rotated just to support humeral head. If this sounds too complicated, again stand in front of the mirror, go into the position you were told to, back and up or back and down, and than try to breathe, lift your arms and rotate your torso. If your scapula position is comprising these actions then you should stop practising it. Remember: whatever you do, it has to be functional!

4. If you are a gym fan and you like to lift heavy, always make sure you warm up your shoulders before a workout and stretch them after.

We often like to sacrifice our shoulder integrity in order to to look good. Hence we spend too much time pumping our biceps and deltoids ignoring all the silent screams coming from the inside of our shoulder joint.

Back to those seventeen muscles – four of those, collectively known as the rotator cuff, stabilise and centre your humerus in the shoulder capsule. They are your prime defenders and you have to keep them alive and active. This is easily achievable by practising the good posture, stretching the right areas (often it’s over-active pectoral muscles), doing some Pilates, manual therapy etc…

If your Rotator cuff muscles aren’t working but you keep on strengthening your big movement muscles, you might end up with incredibly sized biceps but with zero or no movement in your shoulder. Do not sacrifice mobility for size; strength means nothing without stability and good movement.

5. If in doubt – get some help!

As someone who loves and practices manual therapy, I would have to say that shoulder blades are one of my favourite areas in the body to work on. This is in no small part because I think that good manual therapy can make so much tissue change in this region with really good and often immediate impact on the shoulder’s function. All those beautiful articulations, tractions, mobilisations, compressions, trigger point therapies and releases work magic when performed by a good and mindful therapist. If you have a niggle in your shoulder, definitely consider some manual therapy as a part of your shoulder rehabilitation. Plus, having treatment is a great way to maintain your shoulder’s integrity and function even when there is nothing currently wrong with it.